Ever since President Zachary Taylor died suddenly in 1850 after just 16 months in office, many have suspected foul play on the part of his political enemies.

President Zachary Taylor’s death on July 9th, 1850 shocked an uneasy nation. In the years leading up to the Civil War, Taylor had been seen as something of a compromise candidate. But he had a few enemies.

At the time, little suspicion clouded Taylor’s death. Doctors chalked it up to cholera morbus after the president consumed cherries and iced milk during a Fourth of July celebration.

But the elevation of Taylor’s vice president, Millard Fillmore, led some to wonder. What if the president had been poisoned so the vice president could take power?

Zachary Taylor Takes Office In A Tense Nation

As the nation tipped toward violence in the precarious pre-Civil War years, Zachary Taylor emerged as something of a compromise candidate. For one, he was fairly apolitical. Taylor had never cast a vote in his life. Secondly, most Americans knew Taylor as a hero of the Mexican-American War.

Taylor’s service in the Mexican American War proved important. As Americans rallied around “Old Rough and Ready,” they admired different things about his candidacy.

Southerners saw Taylor, a slave-owner from Kentucky, as one of their own. They considered American territorial gains during the war a ripe opportunity to spread the institution of slavery.

But Northerners saw something else. They saw a military man — someone loyal to the Stars and Stripes.

In reality, Taylor was an independent. And, in fact, members of both parties had considered him a possible presidential candidate as his victories in Mexico piled up.

Taylor himself noted that he’d never harbored presidential ambitions. In 1846, two years before his election, he stated that becoming president: “Never entered my head… nor is it likely to enter the head of any sane person.”

Taylor had no strong political leanings either way; but he did have a score to settle. He believed that James K. Polk, the Democratic president, had sabotaged him during a battle in Bueno Vista in order to score political points. A campaign song written for Taylor included the lyrics:

“Polk thought when the war first began How grand he’d be in the story He little dream’d how Zack would rise And carry off the glory!”

Taylor came out as a Whig, albeit, an unenthusiastic one. In a purposely leaked letter to his brother-in-law, Taylor noted: “I am a Whig, but not an ultra Whig.”

The Whigs neatly sidestepped the issue of slavery by presenting Taylor as a candidate “without regard to creeds or principles.” Democrats attacked him as a hypocrite for owning slaves and sneered that he’d been nominated based “solely on the ground of his availability.”

As president, Taylor made his stances more well-known. He threw his support behind the highly controversial Wilmot Proviso, which proposed banning slavery in the new territory acquired during the Mexican-American War.

Southerners were horrified. Taylor met threats of secession with anger. He promised to lead the charge against any states that tried to leave the Union, thundering in February of 1850 to a group of southern leaders that anyone “…in rebellion against the Union, I will hang with less reluctance than I used in hanging deserters and spies in Mexico.”

These were fiery opinions in a fiery time. Taylor had only been in office for just over a year, but he had started to make dangerous enemies.

The Strange And Sudden Death Of Zachary Taylor

On a hot 4th of July in 1850, the president attended Independence Day festivities. He went and saw the newly dedicated grounds for the upcoming Washington Monument and strolled along the Potomac.

During the day, Taylor reportedly consumed cherries and iced milk. Upon returning to the White House, he felt thirsty and drank several glasses of cold water.

By the next day, the president suffered from terrible stomach cramps. Taylor ate slivers of ice for relief as doctors tried to relieve his pain. They gave him opium and calomel, and even tried bleeding the illness out of the president.

Although Taylor momentarily improved — even feeling well enough to write several letters and sign a bill — his condition soon deteriorated.

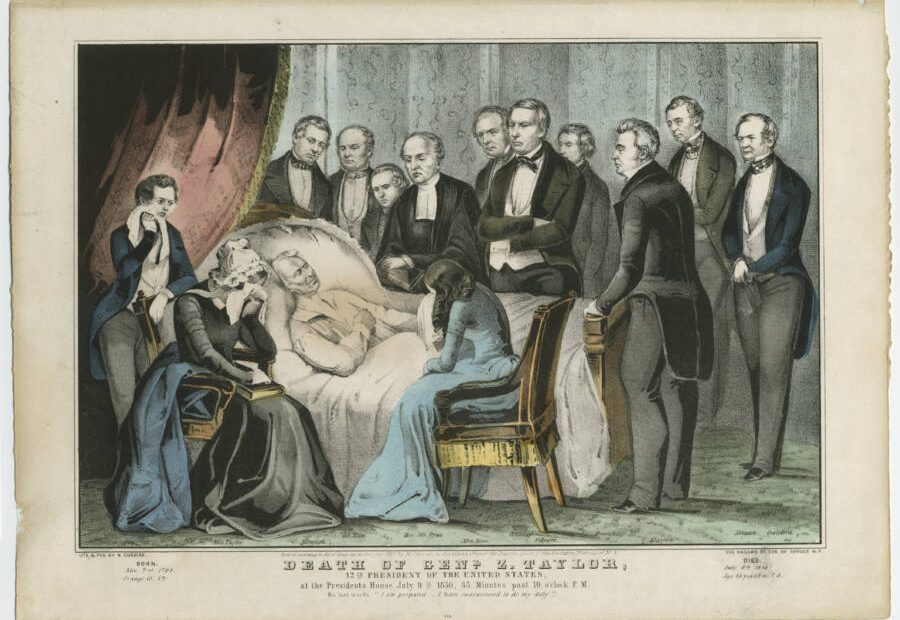

A few days later, the president called his wife to his side. A soldier to the end, Taylor told her: “I have always done my duty, I am ready to die. My only regret is for the friends I leave behind me.”

He died on July 9th, 1850. Zachary Taylor’s doctors blamed cholera morbus, a term doctors used in those days to describe gastroenteritis — inflammation of the intestines caused by bacteria, a virus, or a parasite. Modern doctors believe Taylor became infected due to the poor sanitary conditions in the capital.

After Zachary Taylor’s death, things began to change very quickly. His vice president, Millard Fillmore, was sworn in on July 10, 1850, one day after Taylor died.

Fillmore threw his support to the most controversial issue of the day: a proposed law that would become the Compromise of 1850. Taylor had opposed the compromise.

The law would make concessions to both the North and South, but its most enduring impact was the expansion of the Fugitive Slave Act. The new Act required all citizens to assist in the capture of escaped slaves and offered rewards to federal commissioners for turning in suspected slaves.

So, in even less time than his short presidency had lasted, Taylor’s work toward preventing the spread of slavery was all undone.

Exhuming Taylor In The 1990s

Zachary Taylor’s death remained an oddity of history for more than a century afterward. Most dismissed his untimely and strange death as pure bad luck.

But not Dr. Clara Rising. A historical novelist and former humanities professor at the University of Florida, Rising noticed that Taylor’s symptoms seemed an eerie match to arsenic poisoning.

“Right after his death,” Rising noted, “everything he had worked against came forward and was passed by both houses of Congress.” In Rising’s opinion, Zachary Taylor could have had an enormous impact on American history. Had he lived, he could have prevented, delayed, or “somehow solved the problems” that led to the Civil War, which broke out 10 years later.

In coordination with a coroner and the Department of Veterans Affairs (who oversee the cemetery where Taylor is buried), Rising won approval to exhume the president in 1991 so that Taylor could be tested for arsenic.

Arsenic can last in the body for centuries. If someone had poisoned the president, the evidence could still be discovered.

The results? Zachary Taylor did test positive for arsenic—but only a small amount. If arsenic poison had killed the president, the levels would be 200 or even thousands of times higher.

And thus, Zachary Taylor’s death seems more likely the result of terrible luck — not a stealthy assassin. And after his death, the nation continued its steady march toward war.